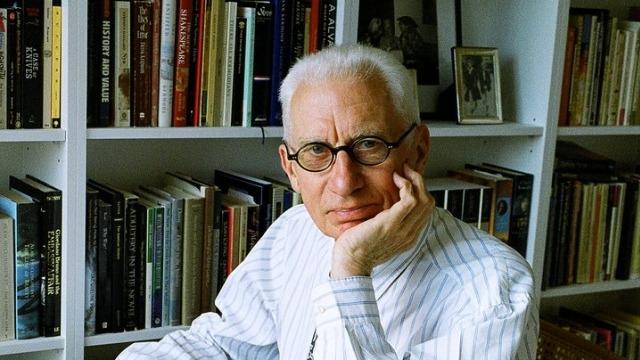

This two-day symposium at the Humanities Research Centre to honour the life and work of the Centre's first Director, the literary humanist, Professor Ian Donaldson (1935-2020), offers a rich array of papers from friends and colleagues exploring a variety of issues to do with literary editing, literary criticism, and literary biography – like Professor Donaldson's own work, largely though not exclusively in the area of early modern studies.

A registration site has been set up on Eventbrite at https://www.eventbrite.com.au/e/a-life-in-literature-a-symposium-in-honour-of-ian-donaldson-tickets-143612574075

DAY ONE: Monday 29 March

8.30-8.40am Acknowledgment of Country and welcome to the HRC (Will Christie)

8.40-9.00am Welcome to the ANU and reminiscences of Ian Donaldson (Paul Pickering)

Opening paper:

9.00-9.45am

Martin Butler (Leeds), ‘Ian and the Cambridge Edition of Ben Jonson’

9.45-10.00am BREAK

10.00-11.30am

Stephanie Trigg (Melbourne), ‘How does Chaucer look? Imagining the author in late medieval poetry’

Simon Haines (CUHK/Ramsay Centre), ‘The Merchant of Venice: liberal sadness and the quality of mercy’

11.30am-12.00pm BREAK

12.00-1.30pm

Francis X. Connor (Wichita), ‘Who am I editing Q1 Romeo and Juliet for?’

Hugh Craig (Newcastle), ‘“It doth, good Mosca”: Short speeches in early modern English drama’

1.30-2.15pm LUNCH

2.15-3.45pm

Ros Smith (ANU), ‘A life in literary criticism: critical approaches to early modern literature, 1974-2021’

Ian Higgins (ANU), ‘Doing the Notes in a Scholarly Edition of Jonathan Swift’

3.45-4.00pm BREAK

4.00-4.45pm

Ian Gadd (Bath Spa), ‘Jeu d’Esprit: Notes on the early modern Stationers’ Register’

DAY TWO: Tuesday 30 March

9.00-10.30am

James Loxley (Edinburgh), ‘One Great Blot: Ben Jonson’s Unemblematic Poetics’

David McInnis (Melbourne), ‘Courting Controversy: The King’s Men and their Patron’

10.30-10.45am BREAK

10.45am-12.15pm

Heather Wolfe (Folger Shakespeare Library), ‘New frontiers in literary editing: The Folger Shakespeare Library’s early modern manuscript transcription project’

Paul Eggert (UNSW and Loyola), ‘Literary Editing in Australia: A short history of the scholarly editing of literary works in Australia, with some personal reflections'

12.15-1.00pm LUNCH

1.00-2.00pm

Peter Holbrook (ACU), ‘The Real in Literature: George Eliot, Virginia Woolf’

Alastair MacLachlan, ‘Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Michael Holroyd and the Defence of Literary Biography’

2.30-2.45pm BREAK

Closing paper

2.45-3.30pm

David Colclough (Queen Mary UL), ‘Whose line is it anyway? The sources of John Donne’s sermons, sacred and profane’

ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES (in alphabetical order)

Ian and the Cambridge Edition of Ben Jonson

MARTIN BUTLER

This paper will describe Ian’s leadership of the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson, looking at its background, its history, and the strategic decisions that were taken in order to carry through its aims and editorial principles. Although large-scale editorial projects supported by long term funding have now become almost commonplace, they were still quite rare enterprises in the academic world of the 1990s. In the absence of many pre-existing models, and the difficulty of sustaining funding over a lengthy period of time, the General Editors were confronted by numerous difficult choices. This paper will particularly focus on some of the problems we grappled with, notably our decision to opt for modern spelling and for a dual publication format in simultaneous print and electronic versions. It will reflect on the consequences of those choices for the edition’s structure and for its afterlife, and compare our experience with that of other large editions recently published or currently in preparation.

Martin Butler is Professor of Renaissance Drama at the School of English, University of Leeds, and a Fellow of the British Academy. His books include Theatre and Crisis 1632-1642 (1984) and The Stuart Court Masque and Political Culture (2008), and he is currently completing a monograph titled Ben Jonson: Man of Letters. With Ian Donaldson and David Bevington, he was General Editor of the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson (2012), and with Matthew Steggle he is General Editor of The Works of John Marston (in progress, for Oxford University Press).

‘Whose line is it anyway? The sources of John Donne’s sermons, sacred and profane’

DAVID COLCLOUGH

This paper emerges from writing the commentaries on John Donne’s sermons preached at St Paul’s Cathedral between 1628-1630. It takes as a case-study a sermon Donne preached in January 1628/9, on the feast of the Conversion of St Paul, and traces his use of two quite different books: one sacred and acknowledged (though not as much as it might have been); the other profane, and unacknowledged. It argues that Donne makes careful and strategic use of these sources to generate a pastoral message appropriate to the occasion and, obliquely, to pass comment on the dangers of divisive religious rhetoric in a highly topical fashion. The paper thus also suggests that what may look to the modern scholar like a rather slapdash attitude to citation can have its own more complex intentions, and that editors therefore benefit from imitating the generosity of spirit as well as the scholarly brilliance that characterised Ian Donaldson.

David Colclough is Professor of Renaissance Studies at Queen Mary University of London. He is the editor of John Donne’s Professional Lives (2003), and the author of Freedom of Speech in Early Stuart England (2005). He edited The Oxford Edition of the Sermons of John Donne, Volume III: Sermons Preached at the Court of Charles I (2013) and is Deputy General Editor for the series. He is currently preparing another volume in that edition, of Donne’s sermons preached at St Paul’s Cathedral, 1628-1630. In the mid-1990s he was a Junior Research Fellow at King’s College, Cambridge, where he was fortunate to be a colleague of Ian Donaldson.

Who am I editing Q1 Romeo and Juliet for?

FRANCIS X. CONNOR

The relationship between Q1 and Q2 Romeo and Juliet is perplexing. Editors trying to resolve the textual issues in these plays have drawn from all of critical editing’s greatest hits: bad quartos, memorial reconstruction, versioning, etc. As an editor of Q1 I have a theoretical narrative of the text, one of course grounded in the work of my editorial predecessors and colleagues, and I look forward to contributing to a conversation that’s been ongoing for centuries.

However, these days I find myself equally concerned with a more immediate audience. The Shakespeare classes I teach attempt to translate the practices of textual editing into critical pedagogy, emphasizing the uncertainties, errors, and cruxes in Shakespeare’s texts. The variant versions of Romeo are a natural fit for the work I want to do with my students. Unfortunately, Q1 Romeo has not found a place in the American Shakespeare curriculum for reasons both practical (no accessible student-friendly text) and intellectual (Q1’s perceived illegitimacy). In part, I think this is a consequence of how textual scholarship has been rendered invisible, leaving the resolution of textual problems to scholars or the deeply curious.

My talk will discuss my theory of the relationship between Q1 and Q2 Romeo, but will also address how future editions of these versions (particularly in print/digital hybrid editions) might present their textual issues in ways that might promote Shakespearean textual pedagogy to a greater variety of readers.

Francis X. Connor is Associate Professor of English at Wichita State University, where he teaches courses in Shakespeare, early modern literature, and the history of the book. An associate editor for the New Oxford Shakespeare, he is currently working on an edition of Q1 Romeo and Juliet for the edition’s Complete Alternative Versions volume. He is the author of Literary Folios and Ideas of the Book in Early Modern England (Palgrave, 2014). More recently he’s working on a project that uses bibliography and textual scholarship to approach a rather different genre: American music fanzines of the 1980s and 1990s.

‘It doth, good Mosca’: Short speeches in early modern English drama

HUGH CRAIG

Most commentary on early modern English plays deals with substantial speeches like persuasions to action, declarations of sentiment, or soliloquies. This is where character, setting and ethos are created and the lyrical, passionate and entertaining language that audiences come to plays for is deployed. If we ask what is the commonest length for speeches in plays from the early part of this period, however, the answer in terms of words is just nine. Moreover, this abruptly changed to four words around the turn of the seventeenth century. This is one of the more surprising quantitative discoveries of recent years, for which we are indebted to the work of Hartmut Ilsemann, Mac Jackson, and Pervez Rizvi. The facts of the case are well established, but there is still much to understand about what might have motivated the change, how it plays out in verse as opposed to prose, which plays and playwrights are exceptions to the rule, and how different the plays look in general if we concentrate on short speeches rather than developed longer contributions. This is an instance of writers working with subtle common constraints, hitherto invisible. Around 1597, presumably without thinking much about it, dramatists favoured speeches of nine words or so. By 1602 the same dramatists favoured speeches of more like four words.

Hugh Craig is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Newcastle, Australia, where he directs the Centre for Literary and Linguistic Computing. He is a Fellow of the Australian Academy of the Humanities. He edited the Literary Record section of the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Ben Jonson Online (2015). His current project is a stylometric study of the Shakespeare First Folio, in collaboration with Professor Gabriel Egan.

Editing in Australia: A short history of the scholarly editing of literary works in Australia, with some personal reflections

PAUL EGGERT

The paper gives an outline history of the scholarly editing of literary works undertaken in Australia or by Australians from the 1860s until the present. It ranges across the principal periods of English literature, finding concentrations of effort in seventeenth- and nineteenth-century literature, and, late in the day, in Australian literature itself. The survey for the first time makes it possible to cast Ian Donaldson’s editorial contributions as part of a more or less continuous tradition of Australian editing, now in the process of crossing into the digital domain.

Paul Eggert FAHA is a scholarly editor, book historian and theorist of the editorial act. His latest monograph is The Work and the Reader in Literary Studies: Scholarly Editing and Book History (Cambridge UP, 2019). It followed Biography of a Book: Henry Lawson’s ‘While the Billy Boils’ (Sydney UP and PennState UP, 2013), and the book he is best known for, Securing the Past: (Cambridge UP, 2009). He was general editor of the Academy Editions of Australian Literature, and he edited titles in the Cambridge Works of D. H. Lawrence and Works of Joseph Conrad series. He is Professor Emeritus at Loyola University Chicago and the University of New South Wales.

Jeu d’Esprit: Notes on the early modern Stationers’ Register

IAN GADD

It was thanks to Ian Donaldson that I first discovered the Stationers’ Register. I was baffled by it then as an undergraduate and, despite almost three decades of researching the Stationers’ Company, the bafflement continues. The Register was created in 1557 by the Stationers’ Company, London’s book trade guild, as a means of managing the publishing rights of its members, and is one of the most oft-cited—and most misunderstood—archival documents of the early modern period. For nearly all the scholars who consult it, their engagement with the Register has been mediated Edward Arber’s magisterial and monumental Transcript(now itself nearly 150 years old) which in turn has become a baffling text in its own right. My talk will use Arber’s edition, his editorial notes, and specifically one unexpectedly literal ‘note’ in the Register itself as ways of exploring its many layers and versions of meaning; it will also reflect on how Giles Bergel and myself built on Arber’s work to create Stationers’ Register Onlineas a new way of searching, reading, and understanding the Stationers’ Register.

Ian Gadd is a Professor of English Literature at Bath Spa University, UK. He studied as an undergraduate at the University of Edinburgh, where he first met Ian Donaldson, and completed a D.Phil. on the Stationers’ Company at the University of Oxford. He was the Munby Fellow in Bibliography at the University of Cambridge and a Research Editor at the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography before taking up a post at Bath Spa University. He has published on the Stationers’ Company and the London and Oxford book trades in the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. He is a General Editor of the Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jonathan Swift and a past President of the Society for the History of Authorship, Reading, and Publishing (SHARP). At Bath Spa University he is also Head of Development for European Projects and the Academic Director for the Global Academy of Liberal Arts (GALA).

The Merchant of Venice: liberal sadness and the quality of mercy

SIMON HAINES

Why is Antonio sad? Because of his hopeless love for Bassanio? Because he’s worried about his ships? Not really: the sadness seems more existential and disabling. Is it a sign of inauthenticity or alienation: some repression of a truer, deeper self? Somehow it goes beyond that too. This feeling is bedrock for Antonio, a sense of absence in the very fabric of himself. From a Hegelian point of view we might ascribe it to a lack of proper “recognition”: this is the “unhappy consciousness” of the master. But Shakespeare isn’t Hegel. This is more like the sadness or satedness of the liberal but resentful man, who lacks neither the recognition of others, nor even a Hegelian mutual recognition, but a true generosity of spirit, originating in himself but moving towards others. Shakespeare’s conception of recognition is unilateral: of an active and responsive giving. The characterisations of Portia (with her own quality of sadness) and Shylock (disrecognisedby everyone else, including her) shed further light on this conception.

Simon Haines is CEO of the Ramsay Centre for Western Civilisation in Sydney. Educated in Iraq, England and Australia, he worked as a banker in London and then as a diplomat and analyst with DFAT and ONA. From 1985-87 he chaired the Budget Committee of the OECD in Paris. From 2009 to 2020 he was Chair Professor of English at The Chinese University of Hong Kong. He is a founding Fellow of the Hong Kong Academy of the Humanities. He was Reader in English, Head of English and later Head of Humanities at the ANU, where he taught from 1990 to 2008. Currently Adjunct Professor at ACU, he is the author or editor of five books including the prizewinning Reader in European Romanticism (Bloomsbury, 2010, 2014), Poetry and Philosophy from Homer to Rousseau (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), and Redemption in Poetry and Philosophy (Baylor, 2013); as well as articles, book chapters and papers on subjects including Shakespeare, Romantic poetry, the modern self, and time in philosophy and art. He was Guest Editor of the Shakespearean International Yearbook 17, Special Section on Shakespeare and Value (Routledge, May 2018).

Doing the Notes in a Scholarly Edition of Jonathan Swift

IAN HIGGINS

This paper considers the theory and practice of annotation – one of the tasks of the editor of a scholarly or critical edition of a literary author. What is it that scholars think they are doing when providing explanatory commentary on the works of their host author? I’ll speak about Swift only because I know something of what a scholarly life is like living on the margins of his pages. The paper will comment on what Swift thought of literary annotation, and on his own practice of annotation as an editor and as a reader of the works of others. I will comment on the annotation practices in some editions produced by Swift’s contemporaries. The paper will conclude with the challenges posed by hitherto unannotated passages from a couple of famous Swiftian texts.

Dr Ian Higgins is a Reader in English at The Australian National University where he teaches courses on British and Irish Literature of the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and on pamphlets and pamphleteering. He was for many years the Head of the English Program. He is a scholar of Jonathan Swift and of the Jacobite era (1688-1780s). He has published two books on Swift, co-edited (with Claude Rawson) three editions of Swift’s writings (for Random House, Norton, and Oxford University Press), and published over thirty essays and articles in scholarly books and journals. He is a foundation general editor of The Cambridge Edition of the Works of Jonathan Swift, 18 vols (2008- in progress) and is co-editing (with Ian Gadd) three volumes in that edition.

The Real in Literature: George Eliot, Virginia Woolf

PETER HOLBROOK

The “Critique of Ideology” in English Literature always involves a certain refusal of theatricality, or falsehood. And this is one of this tradition’s defining virtues: its eye for humbug, attitudinizing, the distortion of truth. In this short paper I want to sketch some occasions where I think this realist stance informs the work of George Eliot and Virginia Woolf (in particular from Middlemarch and from Woolf’s remarkable essay Three Guineas). Both authors seem to appeal to some notion of “reality” as a way of criticizing aspects of their world; so the question must be: “what is this ‘real’ in their writing”? And is it -- whatever it is – in any sense relevant to us today?

Peter Holbrook is Professor of Literature at the Institute for Humanities and Social Sciences, Australian Catholic University, Melbourne. From 1996-2020 he taught at the University of Queensland, Australia, where he was also for a time Professor and Director of the UQ Node of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions (Europe 1100-1800). He remains an honorary research fellow at UQ. His publications include Shakespeare’s Individualism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010) and English Renaissance Tragedy: Ideas of Freedom (London: Bloomsbury, 2015).

One Great Blot: Ben Jonson’s Unemblematic Poetics

JAMES LOXLEY

In bringing his magisterial Life of Jonson to a close, Ian Donaldson noted his subject’s own attempts at making a narrative figure of his life as a dramatist in his late play The Magnetic Lady. Jonson’s recourse to the idea of closing or shutting up the circle has been echoed in attempts by critics and biographers to give shape to the poet’s larger than life existence; but as Donaldson puts it, this ‘is a simplifying narrative, which suppresses the elements of experimentation and also of failure within his dramatic work, suggesting a smooth progression from the start of his theatrical career to its conclusion.’ Taking its bearings from the complementarity of ‘experimentation’ and ‘failure’, this paper will look again at Jonson’s resort to figuration as a way of making sense of the writer’s life in his much-noted adoption of a personal impresa featuring a broken compass, asking how we might read this apparent figure, and whether reading it against the critical grain might help us understand anew what it means for Jonson to experiment, and to fail.

James Loxley is Professor of Early Modern Literature at the University of Edinburgh. He has published widely on many writers and topics in seventeenth century English literature, most notably on Jonson, Marvell and Royalist writing; he has also explored the concept of performativity in a number of publications, and has more recently been involved in innovative developments in digital literary mapping. His current projects include an edition of Thomas Dekker’s The Shoemakers’ Holiday for Arden Early Modern Drama, a monograph on Jonson and the idea of labour, and work on the cultural milieu of Katherine Philips.

Virginia Woolf, Lytton Strachey, Michael Holroyd and the Return of (Literary) Biography

ALASTAIR MacLACHLAN

In his splendid La Trobe University Lecture of 2006: ‘Matters of Life and Death: The Return of Biography’, Ian Donaldson spoke of what he called a ‘surprisingly new cultural phenomenon’, namely The Return of Biography. In it he explored some of the rich variety of contemporary biographical writing. But he also listed a number of anti-biographical ‘dissenters’. And alongside the usual suspects from Paris’s Left Bank and its Anglophone outposts, he listed Virginia Woolf and Lytton Strachey. In this paper, I shall argue that Virginia Woolf’s hostility to biography, fuelled by her rivalry with Lytton Strachey, was more fundamental than he suggested and that she questioned its very legitimacy as a mode of understanding and writing. By way of counterpoint, I shall suggest that Strachey’s hostility was merely limited to its cradle to grave, documentary, Victorian form and by no means ruled out more modern, even post-modern, approaches, reaching back to Aubrey’s brief lives and forward to the innovations listed by Ian in his lecture. Finally I shall consider Strachey’s biographer, Michael Holroyd, as a modernist biographer and on matters of sex a trailblazer, but also something of a throwback. I will end by suggesting that the return of this style of ‘New Biography’ may well prove short-lived.

Alastair MacLachlan is an Emeritus Adjunct of the Humanities Research Centre at the ANU. For many years he was a member of the History Department at Sydney University; he has also taught in Cambridge and Victoria University, New Zealand. He has written on the English Civil Wars, the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, European Nationalism and the English Marxist Historians. He is still trying to finish his book on the historian and ‘Apostle’, G.M. Trevelyan, and his sparring partner, Lytton Strachey, entitled ‘The Pedestal and the Keyhole’.

Courting Controversy: The King’s Men and their Patron

DAVID McINNIS

One of the most puzzling aspects of how Shakespeare’s company conducted its business following the death of Elizabeth and the outbreak of plague is their decision to acquire ‘the tragedie of Gowrie’ – a play about an attempt to assassinate their new patron, James I – for performance sometime in the late autumn of 1604. In this paper, I ask whether that decision might be understood better in the context of a performance choice made two months later in that Christmas season, when the King’s Men offered a play called ‘The Spanish Maze’ at court. No scholar has attempted to offer an educated guess about the specific subject matter likely dramatized in this lost play performed on 11 February 1605 (Shrove Monday), but the possibility I propose – though highly conjectural – is appealing in that it offers a kind of ‘missing link’ between ‘Gowrie’ and Macbeth as plays that engage with political controversy and the king’s interests. Macbeth seems designed to appease the king, with its favourable (though historically inaccurate) portrayal of James’s ancestor Banquo, its oblique allusions to Gunpowder plot associates, and its interest in witchcraft. But Macbeth was not the company’s first or only attempt to capitalise on the identity of their new patron by dramatizing highly personal stories that related to him. In this paper I argue that Shakespeare scholars have credited Macbeth with innovations that had actually been developing over a period of time and a number of plays in the company’s repertory.

David McInnis is Associate Professor of Shakespeare and Early Modern Drama at the University of Melbourne. He is author of Shakespeare and Lost Plays (Cambridge UP, 2021) and Mind-Travelling and Voyage Drama in Early Modern England (Palgrave, 2013), and editor of Dekker’s Old Fortunatus for the Revels Plays series (Manchester UP, 2020). With Matthew Steggle and Misha Teramura, he is co-editor of the Lost Plays Database, which he founded with Roslyn L. Knutson in 2009. He has also edited a number of books, including Lost Plays in Shakespeare’s England (Palgrave, 2014; co-edited with Steggle) and Loss and the Literary Culture of Shakespeare’s Time (Palgrave 2020; co-edited with Knutson and Steggle); Travel and Drama in Early Modern England: The Journeying Play (Cambridge UP, 2018; co-edited with Claire Jowitt); and Tamburlaine: A Critical Reader (Arden Early Modern Drama Guides, 2020). He is currently editing Timon of Athens for the Arden Shakespeare 4th series.

A life in literary criticism: critical approaches to early modern literature, 1974-2021.

ROSALIND SMITH

Since 1974, when Ian Donaldson became the first Director of the Humanities Research Centre, early modern literary studies has followed myriad new directions to become a field that now might seem almost unrecognisable to a scholar from the early 1970s. This paper charts some of the literary movements that have changed the course of studies in our field, focusing on the figure of the author and the category of authorship in early modern women’s writing. New approaches within book history, materialism and formalism, performance and reception, and, most recently, critical race and identity studies, are changing how we approach and understand early modern texts, authorship and cultures of textual exchange. These new literary approaches intersect with digital projects transforming early modern literary studies, building on work that Ian Donaldson, among others, pioneered.

Rosalind Smith is the newly appointed Professor of English at the Australian National University. She specialises in early modern women’s writing, particularly the intersection of gender, politics, history and form, and her books include Sonnets and the English Woman Writer, 1560-1621: The Politics of Absence (2005), Material Cultures of Early Modern Women’s Writing (2014) and Early Modern Women’s Complaint: Gender, Form and Politics (2020). Her current projects include an Australian Research Council future fellowship on Marginalia and the Early Modern Woman Writer, a Linkage grant with State Library Victoria on the recent Emmerson bequest of over 5000 early modern books and manuscripts and her role as general editor of the Palgrave Encyclopedia of Early Modern Women’s Writing.

How does Chaucer look? Imagining the author in late medieval poetry

STEPHANIE TRIGG

Chaucer is one of the first English writers to pay sustained attention to the human face as a subtle means for exploring character. These explorations are grounded in his understanding of medieval rhetorical theory and his translations from French, Italian and Latin works. In the General Prologue to The Canterbury Tales he also deploys humoral language and the medieval science of physiognomy to sketch out individual characters, while in Troilus and Criseyde he uses a full repertoire of facial gestures to dramatize interactions between the three main characters. Throughout his works, Chaucer develops a complex and idiomatic discourse of the face in English to describe facial expression and gesture, to express emotion, character, deception, performativity and truth. This paper examines the complex trope of “looking” (in the twin senses of directing the gaze; and having an appearance) in Chaucer’s representations of himself in his works, and in relation to the emergent iconography of Chaucer as author in the early fifteenth-century manuscripts of his works.

Stephanie Trigg is Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor of English Literature at the University of Melbourne. She is the author of a number of studies of medieval literature and medievalism, including Congenial Souls: Reading Chaucer from Medieval to Postmodern, Shame and Honor: A Vulgar History of the Order of the Garter, and the edited collection, Medievalism and the Gothic in Australian Culture; and more recently, with Thomas A. Prendergast, Affective Medievalism: Love, Abjection and Discontent and 30 Great Myths about Chaucer. She was one of the foundational members of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions. She is currently engaged in a collaborative research program with Guillemette Bolens, Joe Hughes and Tyne Sumner, Literature and the Face: A Critical History.

New frontiers in literary editing: The Folger Shakespeare Library’s early modern manuscript transcription project

HEATHER WOLFE

The Folger Shakespeare Library, in Washington, DC, began a transcription project called EMMO (Early Modern Manuscripts Online) in 2014. The goal of the project was to create trustworthy transcriptions of the Folger’s early modern manuscripts (written in often inscrutable English secretary hand) in order to democratize access to the collection and to provide a counterbalance to the growing number of online full-text searchable early modern printed sources. We did not anticipate in 2014 that we would also be democratizing access to the creation of the transcriptions, and the important role that this knowledge co-creation would play in the development of the project. Although the grant funding for EMMO ended in 2017, our international group of volunteer transcribers had no intention of quitting. Seven years since we began our experiment in crowdsourcing, our community is stronger than ever, with hundreds of volunpeers and pedagogical partners (and their classes) continuing to actively transcribe in our transcription platform. In this talk, I’ll reflect on some of the successes and challenges of opening up the archive and engaging in new forms of knowledge co-creation and think through the status of our transcriptions from an editorial perspective: where does “editing” begin and who counts as an “editor”? If someone wants to create an edition based on our transcriptions (which we hope happens!), how does the editor acknowledge the labor of the transcribers and vetters, who made hundreds of editorial decisions as they converted digital images to eye-readable and machine-readable texts? Are they co-editors?

Heather Wolfe is Curator of Manuscripts at the Folger Shakespeare Library. She currently co-directs the multi-year, $1.5 million research project Before ‘Farm to Table’: Early Modern Foodways and Cultures, a Mellon initiative in collaborative research at the Folger Institute of the Folger Shakespeare Library. Her first book, Elizabeth Cary, Lady Falkland: Life and Letters (2000) received the first annual Josephine Roberts Scholarly Edition Award from the Society for the Study of Early Modern Women. She has written widely on the intersections between manuscript and print culture in early modern England, and edited TheTrevelyon Miscellany of 1608 (2007), The Literary Career and Legacy of Elizabeth Cary (2007), and, with Alan Stewart, Letterwriting in Renaissance England (2004). Her most recent research explores the archival history of Shakespeare’s coat of arms, and the social circulation of early modern writing paper and blank books in England. Her essay “The Material Culture of Record-Keeping in Early Modern England,” co-written with Peter Stallybrass, received the 2019 Archival History Article Award from the Society of American Archivists. She received her BA from Amherst College, her MLIS from UCLA, and her PhD from the University of Cambridge.